“I HAVE DEFINITELY SEEN A RESURGENCE OF INDIGENOUS FOLKS RECONNECTING AND LEARNING ABOUT THE OLD WAYS” – HUEY ITZTEKWANOTL O))) (TZOMPANTLI)

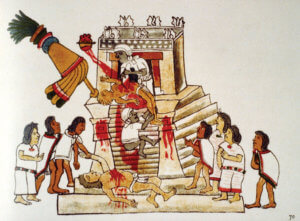

Honouring, celebrating and invoking the might, majesty and oftentimes brutality of the Mesoamerican people, Tzompantli’s intoxicating breed of distinctive death doom, as evidenced on debut full-length, ‘Tlazcaltiliztli’, is distinguished by the inspired deployment of native pre-Hispanic folk instrumentation. Huey Itztekwanotl o))) – the primary creative entity behind this primitive, ritualistic yet poignant conjuration – discusses the extraction and ceremonial offering of human hearts [Eltequi]; displaying human skulls on racks [Tzompantli]; nourishing the fire with sun and blood [Tlazcaltiliztli]; sacrificial bloodletting to appease the Mexica gods; laments the near-obliteration of his ancient ancestors’ traditional customs and practices by ignorant outsiders; and vows to live his life in opposition to colonial powers.

An orchestra of unorthodox instrumentation is very effectively deployed on Tzompantli’s debut full-length, ‘Tlazcaltiliztli’. Could you disclose which indigenous instruments you opted to use and perhaps provide some information on their origins and their particular significance to you as musicians?

An orchestra of unorthodox instrumentation is very effectively deployed on Tzompantli’s debut full-length, ‘Tlazcaltiliztli’. Could you disclose which indigenous instruments you opted to use and perhaps provide some information on their origins and their particular significance to you as musicians?

“We used huēhuētl, which is a percussion instrument not too different from the floor tom, as well as a teponaztli, which is a hollow wood log with slits. These were used in celebrations or communications during wartime. I also used some animal flutes and the death whistles, which were to help guide the sacrifices to the underworld / afterlife. I used shells and shakers to help keep the beat. In my head, I am a drummer first and foremost, so layering and creating percussion rhythms is one of my favourite things to do as a musician.”

How important is it to play these native folk instruments in the manner in which they were originally intended to be used and how challenging was it to seamlessly blend such uncommon sounds into a predominantly Death Metal soundscape?

“It’s very important when I think ‘these are instruments my ancestors used’ and it gives me a deeper connection with and understanding of them. I don’t find it challenging really … like I said I feel like I’m a drummer first, so percussion comes very easy to me. I am just taking the sounds and using them for a more modern time by throwing some heavy ass guitars over them.”

Where do you source the more unconventional equipment? Do you have to seek out vintage antiques or are there people still manufacturing traditional Aztec drums, flutes, whistles and shakers today? Have you ever modified, refurbished or built your own instruments?

Where do you source the more unconventional equipment? Do you have to seek out vintage antiques or are there people still manufacturing traditional Aztec drums, flutes, whistles and shakers today? Have you ever modified, refurbished or built your own instruments?

“The huēhuētl was borrowed from a close homie but all the rest of the instrumentation are ones that I own and have practiced. I am always seeking out instruments when I can afford them. I wouldn’t say my collection is too impressive but it is slowly growing. I will usually find people online or at gatherings that sell them. Unfortunately, I am not good at modding or building my own shit, haha.”

At the centre of ‘Tlazcaltiliztli’ lies the ultra-ritualistic and utterly intoxicating tribal instrumental ‘Eltequi’, which borrows its title from a rather delightful sacrificial ritual of cutting out the heart and serving it up as an offering. Under what sort of circumstances would the ancient people of Mesoamerica have performed this ritual? Are you aware of any instances of Eltequi being executed in more modern times?

“No, I am not aware of Eltequi happening in modern times. But this was a common practice for some of the big ceremonies that revolved around Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli. Mostly during seasonal changes, if I remember correctly. I will say, ‘Eltequi’ is one of my favourite songs I have ever written and recorded.”

Equally visceral, Tzompantli derives its name from a rack that was used to display human skulls – often those of sacrificed enemies or war captives. Like Eltequi, this is another reference to the potential savagery and ritualism of the Mexica people. These tribes were not to be messed with! Were these kinds of events and displays commonplace or were the Mesoamericans generally a peaceful, structured and disciplined civilisation? Were they offerings to the gods or punitive measures to maintain stability and societal harmony?

“Tzompantlis were used by several different Mesoamerican cultures. They were common, sometimes after ritual sacrifices or after a ball game, they would include the losing team’s heads. I believe they were for both. Human life was very valuable and precious to the Mesoamericans; a life sacrificed is always offered up to the gods and never for nothing.”

Tlazcaltiliztli is a(nother) ritual ceremony translating as ‘nourishing the fire and sun with blood’. Can you tell me any more about this? Fire and smoke were very important in Mesoamerican ritual practices, I believe, the former seen as an important force in transformation. Like most other ancient civilisations, the Mesoamericans had a great respect for the elements and the natural world that sustained and nourished them – modern man (motivated more by control, manipulation, validation and exploitation) could learn some lessons from this…

Tlazcaltiliztli is a(nother) ritual ceremony translating as ‘nourishing the fire and sun with blood’. Can you tell me any more about this? Fire and smoke were very important in Mesoamerican ritual practices, I believe, the former seen as an important force in transformation. Like most other ancient civilisations, the Mesoamericans had a great respect for the elements and the natural world that sustained and nourished them – modern man (motivated more by control, manipulation, validation and exploitation) could learn some lessons from this…

“Nourishing the fire and sun with blood was the most common practice. Most of it was done by bloodletting in various ways, depending on the culture, and burning the blood which is feeding the fire so smoke would go upwards towards the sun. For the Mexica, the sun was their primary source of worship.”

As well as brutality, a poignancy and sense of sorrow also pervades the seven sacrificial offerings that comprise ‘Tlazcaltiliztli’. What is the source of this anguish and melancholy? Are you lamenting the mindless eradication of your ancestors from bygone times and the permanent loss of the bounty of wisdom, tradition and intuition that was extinguished along with them? The parting shot, ‘Yaotiacahuanetzli’, is the most sorrowful – what is the prevailing theme of this song?

“I have always been a fan of sad music, which is why I got drawn to doom metal back in the day. But I would say that when writing songs about, for and with my ancestors in mind, there’s definitely going to be some sadness involved. With the song ‘Yaotiacahuanetzli’ (warrior’s blood), it’s a reference or story of the life of a Mexica warrior. It ends with what we believe happens after they pass on, which is feasting and flying.”

There exist some stellar extreme metal acts promoting indigenous / Native American themes in their art. Blue Hummingbird on the Left, Ifernach, Pan-Amerikan Native Front, Maquahuitl and of course Xibalba – with whom you enjoy close ties – all create exceptional music. Are you familiar with these bands and their message? Are there some others you would recommend?

“I am very familiar with these bands. I do enjoy them and have had the pleasure of seeing a few of them live. Some other indigenous / native acts I like are Ixachitlan, Volahn, Muknal and Homeland, as well as others under the Crepúsculo Negro (Black Twilight Circle) and Night of the Pale Moon banners.”

Do you harbour resentment towards the outsiders or conquistadores who came into your lands all those centuries ago, displaced the native Mesoamerican people and changed the course of history there? The theme of invaders annexing a foreign land and claiming it as their own, with no tolerance of local tradition, is a familiar one throughout history. Suddenly, it is the natives who are treated as outsiders. But this was not a ‘New World’. The pre-Hispanic indigenous people had already established advanced civilizations with cities and towering architectural monuments as well as complex writing systems and a radical understanding of astronomy. Seems they were doing just fine before Columbus arrived? And things could hardly have been any worse than they are on the American continents today?

“There’s resentment there, for sure. I wonder how great our civilizations would’ve become and the great things we could’ve accomplished. So yeah, we were doing just fine without the colonial shitbags. All I can do is live my life in opposition to the colonial powers that be and spread awareness that we are still here and we reign.”

The natives were forced to convert from their pagan beliefs to the plague of Christianity and devout Catholicism has spread like wildfire throughout the Americas. Was that the ultimate ignominy?

“I believe so. It was a way to subjugate and control our people. I will say, I do love that as each year passes (in these modern times), the number of people that believe in these false religions continue to drop.”

Modern descendants of the Maya still live in Central America in modern-day Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and parts of Mexico. I have no idea to what extent they practise ancient customs (I would assume many of them have been outlawed), but is it possible to keep alive and perhaps even resurrect some Mesoamerican / pre-Hispanic traditions? With a clear globalist agenda at play across the world and an orchestrated mass migration of people, are you concerned that things are moving in the opposite direction – towards the erosion of all ethnicities?

Modern descendants of the Maya still live in Central America in modern-day Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and parts of Mexico. I have no idea to what extent they practise ancient customs (I would assume many of them have been outlawed), but is it possible to keep alive and perhaps even resurrect some Mesoamerican / pre-Hispanic traditions? With a clear globalist agenda at play across the world and an orchestrated mass migration of people, are you concerned that things are moving in the opposite direction – towards the erosion of all ethnicities?

“I have definitely seen a resurgence of indigenous folks reconnecting and learning about the old ways. I believe we can still keep them going regardless of what is going on on a global scale. Europeans have tried to erode our cultures but we are still here.”

Would you agree that once we lose sight of our culture, our heritage and our sense of Nation that we have been spiritually amputated? Modern man is weak and soulless compared to older civilisations, no longer at one with nature or aware of his place in it, ignorant of his natural connection to the very soil that sustains him. A man should be anchored in the earth, naturally rooted and embedded there by his past and lineage. Bit by bit, this connection with the past is being destroyed and dismantled. Will humans wake up and put down our smart phones, get back to basics and reconnect with our pasts, our cultures, our lands? Or has humanity (d)evolved beyond the point of no return?

“I would agree for the most part but I would refer back to the previous answer about the resurgence of indigenous / natives that are reconnecting to their roots. This isn’t just happening on Turtle Island. A lot of the world is starting to wake up and realize that colonization was and is bullshit. It has created systems that do not benefit them or allow them to be in touch with who they are or who their ancestors are.”

Perhaps a day of reckoning is coming soon, which could herald great change, some of it for the better. The world is in a very volatile and precarious position right now and it’s hard to shake the feeling that something monumental is about to happen. Our civilisation could be on the brink of extinction … society has been dumbed down to such an extent that it might not be that big a loss…

“All we can do is decolonize our minds and keep living.”